By David Stockman of David Stockman’s Contra Corner.

In February 2004, Ben Bernanke famously declared the business cycle had been tamed and took a bow on behalf of enlightened monetary management, claiming it was the principal source of this beneficent development. Exactly 55 months later, of course, he terrorized the congressional leadership and a clueless president with the frightening proposition that a Great Depression 2.0 was just around the corner.

As to why he had been so stupendously wrong, Bernanke did not say. Nor did he explain why the brilliantly “stable” US economy had suddenly stumbled to the edge of an abyss despite the Fed’s energetic money printing in the interim. And the Fed had not been stingy in the slightest; its balance sheet had actually expanded by $150 billion or nearly 4.5% annually between February 2004 and the Lehman bankruptcy.

Indeed, six and one-half years on from the financial crisis—events that made a mockery of the Great Moderation—the monetary politburo and its acolytes on Wall Street have offered no coherent explanation as to why Armageddon loomed nigh and why the worst business cycle plunge since the 1930s actually materialized. Certainly their lame Monday morning claim that “prudential regulation” had failed doesn’t cut it.

Indeed, depicted below is the staggering growth of household debt in the U.S. economy between the two signal financial events of this century—the dot-com bust and the Lehman meltdown. Households borrowed themselves silly during that period, extracting upwards of $3 trillion of MEW (mortgage equity withdrawal) from their home ATM machines, among other delusionary outbreaks. Yet to say that this borrowing binge was caused by inadequate bank supervision is an insult to intelligence. It might as well be argued that the “financial contagion” that fueled the crisis arrived on a mysterious comet from deep space!

In fact, the eruption of $7 trillion of new household borrowing during this period—or more than all the household debt outstanding at the turn of the century—is the work of the central bank. It was the Fed’s 1% interest rates and stock market puts that had already triggered the housing and mortgage frenzy, even as Bernanke boasted about its management prowess in February 2004.

Never having explained the causes of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) or acknowledged its own evident complicity, the Fed has nevertheless energetically doubled down on the same monetary toxins that caused the last crisis. In fact, between the September 2008 plunge that Bernanke said couldn’t happen and the plunge lurking just around the corner once again in March 2015, the Fed’s balance sheet has soared by 4.5X or at a 27% CAGR for nearly seven years running.

So now the third immense financial bubble of this century has been fully inflated. And there are abundant signs that what we really have is a Great Immoderation—a baleful, not beneficent, development that can be laid exactly at the door step of the central bank.

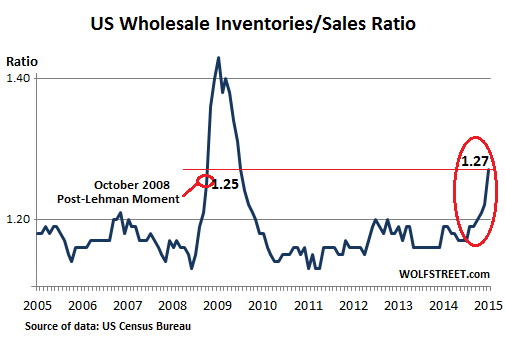

Specifically, yesterday’s abysmal data on the soaring wholesale sales/inventory ratio (I/S ratio) is not only a sharp stick in the eye to the “escape velocity” chatter that emerged in last year for the fifth year running; it also offers crucial insight into a issue that the Fed and its partisans incessantly gum about but never get right. Namely, the matter of monetary policy transmission—or the pathways through which the Fed’s interest rate manipulations, balance sheet expansions and verbal guidance work their way into the wider financial system and macro-economy.

The long and short of it is this: The credit channel of monetary policy transmission has long been over and done because the U.S. economy has reached a condition of peak debt. But since the posse of Keynesians who inhabit the Eccles Building refuse to acknowledge this cardinal fact and persist in pushing on a string of massive monetary stimulus, a new channel of policy transmission has been carved out of what was once a healthy financial and business system in the U.S.

Call that new transmission channel the “C-suite in bull market heat”. The obvious but never acknowledged fact of business life in today’s central bank dominated world is that top corporate executives no longer really manage their companies’ organizations and operations; they mostly manage corporate stock prices and their own option-based incentive programs.

If you want some evidence, just consider the facts I cited Monday about the disposition of net profits by the S&P 500 companies. During the LTM (last twelve month) period ending in Q3 2014, they generated $945 billion of net income and flushed $895 billion, or 95% of that total, back into the Wall Street casino in the form of stock buybacks and dividends.

In light of those stunning numbers, don’t you think CEOs have stock prices and option values constantly on their brains? Yes, they do. Otherwise you can’t explain the next number, either. By the end of the current quarter, CEOs and boards will have flushed the staggering sum of $4 trillion in dividends and stock repurchases back into the market, or 85% of the earnings of the 500 largest companies domiciled in America since the March 2009 bottom.

So the truth is, the new channel of monetary policy transmission in this era of money printing madness runs through the C-suite. And after the giant financial bubbles and busts during this century—it is also now evident that this new transmission channel is radically and violently pro-cyclical. That is, it does not level the business cycle—it drastically amplifies its oscillations.

As shown below, during the run-up to the GFC, the amount of cash being flushed into the stock market soared; and this rise reflected an amplitude of gain far greater than the rate of earnings growth during the period. But almost immediately after the S&P 500 index peaked at about 1570 in October 2007, the level of buybacks and dividend distributions began to fall—and then plummeted with a rush during the financial crisis and Great Recession of 2008-2009. By the bottom quarter in 2009, the amount of cash being pumped into the stock market was running at only $85 billion per quarter, or just one-third of its peak rate.

Needless to say, history is now repeating itself, and the reason is not hard to find. During the third quarter of 2009, as the economy began to rebound, the S&P 500 companies distributed just 63 percent of their net income as dividends and buybacks. By contrast, five years later after a 200% increase in the stock index, the S&P 500 companies distributed $234 billion out of $244 billion of net income.

That’s right. Last fall the C-suite was in such intense bullish heat that it distributed 96% of earnings to the clamoring throngs in the casino. America’s corporate executives could think, apparently, of nothing else but their stock prices and bonuses.

Needless to say, when this big fat C-suite “bid” evaporates, the props are pulled out from under the stock market. And, most especially, the chart points used by the robo-traders and dip buyers fail—causing the kind of violent plunge that occurred in the NASDAQ during March-April 2000 and the broader market from Lehman event through the March 2009 bottom.

Unfortunately, however, that’s not the half of it. As the Fed reflates the financial market after each bust via free carry trade funding for stock speculators and massive liquidity injections into the canyons of Wall Street, the incessantly rising stock averages not only induce the self-reinforcing waves of stock buybacks and dividend payouts shown above, but also cause a second and equally counter-productive pro-cyclical behavior.

To wit, as stock market-obsessed executives become ever more confident about the financial cycle, they succumb to the “this time is different” mentality that infects the entire casino—not the least because their minds dwell in the casino most of the time. Accordingly, top management steadily loosens the corporate purse strings and permits their operating executives to accumulate excessive inventories of labor and production goods and supplies on the expectation that the real economy will soon follow the stock market into the stratosphere.

At some point, however, realty protrudes. When the boom in sales eventually fails to materialize, companies find themselves overstocked with labor and physical inventories—and vulnerable to some confidence shattering event such as the Lehman bankruptcy—that triggers a sharp liquidation of these excesses.

That’s essentially what is now emerging in the current I/S ratios. As Wolf Richter cogently pointed out in his post today, we have suddenly—only a few months after “escape velocity” was a sure thing—seen the I/S ratio soar to its October 2008 level.

In point of fact, the Great Recession was actually a short but massive burst of inventory liquidation emanating from the same C-suites that had reached a peak of bullish fever in late 2007. Contrary to Bernanke, the September 2008 plunge had nothing whatsoever to do with a relapse toward the Great Depression and an unstoppable downward spiral into an economic abyss.

Instead, shorn of their bullish enthusiasm owing to the collapse of their stock prices, business executives liquidated the excesses that had built up during the Greenspan-Bernanke bull run. Using the data on wholesale inventories as a proxy, the chart below shows that over 80 month expansion from the cyclical bottom in April 2002, inventories rose by $165 billion, or nearly 60%.

But during the 12 months after August 2008, nearly half of that accumulation was liquidated. Then the slow process of rebuilding commenced once again. Moreover, the hook upward that became evident by November 2009 had virtually nothing to do with the Fed’s panicked money printing during this period. At the point in late 2009 when the inventory liquidation ended, business and household credit—the only thing that ZIRP could directly influence—were still shrinking.

Stated differently, after having experienced the fear of god, the C-suite had sobered up and had recommenced running their businesses, not merely their stock prices. The recovery was owing to the regenerative capacity of capitalism, not the speed of the central bank printing presses.

The data for the excess inventories of labor are nearly identical during this cycle. During the period between September 2008 and September 2009, the frightened inhabitants of the C-suites off-loaded labor at a violent rate. During those months, the BLS establishment survey—dubious as it is—showed an average reduction of nearly 600,000 jobs per month. Yet by the last three months of 2009, it was all over but the shouting. The BLS job loss rate shifted down sharply to 100,000 per month until excess labor inventories had been fully liquidated by early 2010. Again, money printing had nothing to do with the process of bottoming and reversal.

At that point, in fact, American capitalism might have had an opportunity to heal itself and commence on a long march toward sustainable growth and real wealth gains. But the monetary politburo would have none of it—keeping the pedal to the metal until this very moment.

So the rest is history—repeating itself. The Fed and the other central banks around the world have fomented a new and even more virulent and dangerous financial bubble. The C-suite has once again plunged into a fevered bullish heat and has once again permitted excess inventories of goods and labor to build on company balance sheets. That’s why the BLS keeps reporting big job gains each month.

But those Jobs Friday gains are not evidence of escape velocity, sustainable recovery or the approach of the Keynesian nirvana of permanent full-employment.

No, its just another outbreak of the Great Immoderation. And we already know what happens next.

Seth Mason, Charleston SC